- Home

- Donna Hemans

Tea by the Sea Page 8

Tea by the Sea Read online

Page 8

5

Lenworth should not have been hers. Plum didn’t tell his mother that detail, nor did she tell how she and Lenworth met. Plum saved for herself the little details: she and Lenworth on the verandah of her aunt’s house in Discovery Bay, Plum stealing glances at her tutor’s generous eyebrows, his milky-brown complexion, heavy eyelids, eyes more round than oval and the goatee framing his chin. He was twenty-three, she sixteen, and by her calculation appropriately-aged—barely an adult but still worlds away from the boys her age.

Plum kept to herself how she first lost Lenworth during the Easter break, not long after they met. A complete misunderstanding of the adults. That Easter afternoon, boys across the neighborhood flew homemade kites, which whooped and buzzed as they dipped and rose, sometimes as delicately as a bird and sometimes with exaggerated swoops. Plum sat in the front yard, beneath the expansive almond tree.

Lenworth tried to project a serious voice, to distract her from the kites’ buzzing and whooping. But Plum, sixteen years old, had a teen’s apathy toward algebra and trigonometry and chemistry. And she had even greater apathy toward the adults inside—her aunt Dolores, or Didi for short, and her parents, who recently flew to Jamaica from Brooklyn to check on her progress and see for themselves whether she deserved the reward they dangled: spending the entire summer vacation in New York.

Inside, Plum’s aunt distilled the stories her parents had heard in lesser detail by phone and letter. Plum had no voice in the storytelling, and was too distracted by the kites’ coordinated dips and swoops to think too much about what her aunt would be saying and her parents comprehending.

Lenworth, realizing the futility of continuing, put the book aside. “What is it?”

“What?”

“No use in wasting their money or my time.”

Plum stood, shook the cramps out of her legs, and pressed her toes into the soft grass. “They already expect the worst of me anyway,” she said.

“All right then. Get it off your chest so we can continue.” Lenworth put the books down and listened to Plum tell of being sent away like a bag of old clothes, unwanted and useless.

“Agency,” Lenworth had said. He leaned back on the grass, his palms cupping his head, his toes pointed upward. “You and me both. We learn early what it means to have no agency and the exact opposite of it.”

“Agency?” Plum pondered the word.

“Yes. Control over your life.”

Perhaps it was the dizzying movement of the kites, the afternoon breeze coming off the nearby sea, the ease with which they spoke, but neither heard the adults stepping outside onto the tiled verandah or padding barefoot across the grass.

“Really!” Dolores’s voice was high. “This what I paying you for, to loll about on the grass like tourist on holiday?”

“I was just explaining,” Lenworth began.

“Explaining what? That’s how you do math? I know she don’t want to do the work but you should know better. I not paying you to be her friend. I paying you to teach the girl, to help her pass the exams.” She turned around, not easing her voice, and repeated it all, as if Plum’s parents hadn’t also witnessed him lying about looking out from under the tree canopy at the kites, the dizzying movement of color against the blue sky.

“It’s just . . .” is all he could say, for her aunt didn’t let up, didn’t pull back her harsh criticism of lazy loafers who want to get by without doing the work.

“Don’t even think I paying you for today. Don’t even think it.”

“It’s just . . .” he said again.

“You still here. Pack up your things and leave. Go.”

And so Lenworth went out of her life as quickly as he had come.

Plum didn’t think about his absence until a September afternoon, five months later, when he reappeared under the jacaranda tree at her school, sipping and spitting up a milky tea. By then, she was seventeen, in her last year of high school and imaging herself a woman living a life somewhere other than Discovery Bay, and he, a temporary assistant in the chemistry lab, working there to save toward his engineering degree. They picked up where they left off that Easter afternoon, bonding over tea and building a friendship that hadn’t fully taken off during their first meetings, resurrecting it and letting it mature in secret.

He had taken to eating his lunch under the jacaranda tree and sipping hot tea in the afternoon sun. Though inexplicable to Plum, the hot drink in the hot afternoon cooled him. The afternoon they met again, the kitchen staff had got his tea wrong; it was sweetened with condensed milk. She caught him with spit dribbling on his chin, and without a tissue or a handkerchief to wipe it away. She smiled and handed him a tissue.

“Too bitter?” she asked.

“Condensed milk. I hate the taste of it.”

“It’s too hot for tea anyway.”

“The hot drink cools your body down.”

“No way.”

“I teach science, remember?” He smiled as he spoke. “I read it in a magazine. If you drink a hot drink, it lowers the amount of heat stored inside your body. And it causes you to sweat more. You know this part. Sweat cools your body.”

Plum raised her eyebrows. “Really.”

“It’s simple. A hot drink makes you sweat and sweat cools the body.”

Plum sat on the empty corner of the bench, stretching her legs out before her as if settling in for a long afternoon’s rest. “Fruit teas are better,” she said. “Orange, sorrel. And ginger root. I can’t have it here, of course. But it’s the one thing that would make my life at this school a little bit better.”

So day after day he brought her tea in a thermos, and the two oblivious to or unconcerned about gossip from students, sipped fruit or ginger tea together under the jacaranda tree. The bench where they sat looked down on the town sprawled below, the rusting zinc sheets atop the buildings, the minibuses picking up and dropping off passengers, higglers at the market haggling over produce and fruit and discount wares. Like a prisoner teased with freedom, Plum looked down on a whole life outside the gates of the school that she, as a boarder, sampled only on the third weekend when the boarders left the school for home. She longed to be back in Brooklyn, free to wander after school, free to stop in a shop for a candy bar or soda or pizza.

The ease with which they talked. Of her school. Of her parents. Of her wish to be back in Brooklyn, if only for an Easter or Christmas dinner, in a house overrun with family and friends, cousins fighting over toys that weren’t theirs, her father’s and uncles’ boisterous laughter booming over the din of the television. Of his dream to build a bridge to replace the island’s infamous Flat Bridge, which could accommodate a single line of traffic at a time and which flooded several times a year when heavy rain and debris swelled the river that flowed beneath. He imagined a replacement bridge with a higher clearance above the water or a crossing at another point in the gorge.

He liked the way she spoke, the hint of a foreign accent, her matter-of-fact manner. She didn’t say “mister” or “sir” as the other students did, but spoke to him as if they were equals, not teacher and student, not liberated adult and young adult. Yet, they weren’t equal. She was a student, not directly his student, but a student nonetheless, and a child he had once tutored at her aunt’s request.

What shouldn’t have begun, began as an afternoon kiss on the beach on one of Plum’s weekends home with her aunt in Discovery Bay. A simple kiss near a sea grape tree on a beach used mostly by fishermen. Plum, never shy, turned shy, then bold again. He, never much of a romantic, driven mostly by an urge to build objects from useless things, became a different man, one emboldened, capable now of feeling love. Plum was everything he hadn’t known.

Plum had only one tangible memory of that outing, a photo of Lenworth standing with his back to the water, his hands akimbo. She kept the photo in a tin with one other piece of paper that connected her to her early life with him. In reality, she had mimicked his pose, laughing as she did. But Plum didn’t hav

e that corresponding photo of her, her eyes nearly closed, her head thrown back and the length of her neck exposed. Beach outings on Plum’s free weekends home became their thing. Plum liked the quiet mornings on the beach. It was the one outing to which her aunt didn’t object because she understood the confines of boarding school life and the freedom of looking at and moving in the open sea. Besides, her aunt knew the woman who managed the beach, and she trusted that there Plum would be safe. And Lenworth made it his thing too, sometimes bringing sugar buns or plantain tarts for their early beachside breakfasts. If there were adults around, like the woman who managed the beach, he pretended that he had come for the water aerobics class.

The ease with which they played, romping on the sand like carefree children or lovers, she stopping where the waves brushed up against the sand, too afraid of the tangle of moss on the sea bed to wade into the water after him, he swimming out and waving from a distance, beckoning for her to join him. Sometimes if they were on the side of the beach where the moss wasn’t a thick bed on the floor, she did.

Another Easter weekend, they had gone to Puerto Seco Beach, which on an Easter day was overrun with children and adults who had waited all year for the Easter Monday beach outing. So they had walked away from that public beach, around the broken fence to the free beach, past the lone fisherman mending a boat and the others who had come to the free beach rather than pay to swim and play at the moss-free, rock-free beach, and on to the edge of the community of villas perched on rocks above the coastline.

Her T-shirt, wet then, flattened against her stomach, and he saw for the first time the outline of her swelling belly.

The ease with which they fought. Because she hadn’t told him. Because she had waited too long (three months along, she thought). Because her life, and his, would be utterly and completely altered.

But they made a plan. He went back with Plum to her aunt’s house, the very house from which he had once been expelled and forced out of her life. Plum changed from a sundress to a T-shirt and shorts. Her belly was pressed delicately against a white T-shirt, the baby announcing itself to the world.

“Lawd, Jesus.” Plum’s Aunt Didi threw up her hands. “Look what trouble you bring here now. This is what you come to tell me?” She didn’t wait for Lenworth to answer. “Child, how far along are you? Four, five months?” Plum’s answer wasn’t what she wanted. “You talk to your parents? They need to know before they come down here for your graduation and come to see this. Lawd.”

She turned to Lenworth. “You better have something good to say, because this is not what I hired you for. You know what, you better leave. Just leave. Go. You can deal with her father when he comes.”

Plum kept quiet. Her aunt didn’t know, and Plum didn’t reveal, that she and Lenworth had reconnected because of his work at her school. She preferred to let her aunt and her parents believe that she had defied their wishes and continued to see Lenworth in private. Her parents punished Plum’s defiance. They didn’t come at all for her graduation, simply cancelled their tickets and Plum’s return ticket, leaving her to make her way with him, and leaving him without a platform from which to speak his intentions. Not that his intentions mattered in the end.

6

Had Plum found Lenworth and come to Anchovy then, she would have found a tomboyish girl with dimples like Plum’s, almond-shaped eyes that were too brown to belong to someone with such dark skin. Had Plum come then, she would have found a not-yet-sophisticated Pauline worrying about the plumbing in the old house, the tank nearly empty of water, the duck ants again making nests along the wall, the springy floor boards in the tiny living room, termites that were slowly eating away the wood in the house. And she would have found the little girl who would not smile at Pauline, the tomboy of a girl who wandered off with the neighborhood boys as if there was something out beyond the house waiting to be found by her.

And she would have found Lenworth embroiled in another scandal, the circumstances somewhat similar to hers: a school employee and a student caught up in a friendship that seemed too close, a school staff rooting around for the truth, a girl clamming up and protecting him to the very end, and Pauline aware of the sketchy details of the school’s inquiry, boiling with anger.

The house in Anchovy was too close, too small really to contain both Pauline’s explosive anger and Lenworth’s fear of exposure, without the two competing emotions surging and spiraling into a cataclysmic encounter.

Pauline, heavily pregnant and rocking her first-born, Craig, yelled through an open window, alternating between cooing and whispering to the frightened two-year-old and pressing her enormous belly against the window frame as if to catapult her words through the louvers. Pauline and Lenworth had forgotten Opal, who was too young to understand the nature of the quarrel, the possible loss of his carpentering job and too scared to move. So she stood still, a shadow in the shadows, a mute within the muted rooms, tears dripping down her face, her fingers laced together, her feet as stiff as a statue’s. She wanted to go to him, the quiet one, but couldn’t get her feet to move from within the shadows and propel her body through the lit dining room within reach of Pauline’s voice and out to the verandah where her father sat. Opal stayed in the dark, uncomforted, neither savior nor saved.

In truth, Lenworth’s situation with the student was not at all the same as his relationship with Plum. The facts that he should have told Pauline: The girl had taken to stopping by his campus workshop on a daily basis. He didn’t turn her away. The girl’s mother had found a letter to him and she refused to believe that nothing untoward had happened between her daughter and him. Lenworth thought it best to keep quiet lest someone dig deep and find out about him and Plum, the circumstances under which he had left his previous teaching job, and how he had left Brown’s Town with the baby girl, how he had abandoned the baby’s mother in the hospital.

Instead of fighting and risking exposure, he had walked away from the job and the school and into a verbal brawl with Pauline.

Lenworth stayed outside, still in the shadows, watered by the night’s dew, weighing the mistakes of his young life like a ball he rolled from one palm to another. Long after Pauline’s rage had subsided and the children had gone to sleep, he slipped into the old chicken coop he’d converted into a workshop and lay down on the new sawdust—cedar and mahogany and pine commingled—which only a day earlier he’d laid down like a bed of moss on the dirt. The limbs of a cherry tree brushed across the roof, and in the distance an owl hooted. Much closer, the night insects chirped away, unconcerned with the other life forms quieting themselves and bedding down for the night. The sky, clear and cloudless, glittered like a sequined dress. He couldn’t see anything beyond the circle illuminated by the oil lamp, but he wasn’t concerned with the imagined or real thing that lay out there beyond the converted chicken coop. An old sewing machine, whose tabletop had been devoured by termites, stood before the worktable. He envisioned the scrolled metal legs, with Singer stamped across the back support, as part of something else, living a new life far removed from its former one. He hadn’t yet determined what it would become. The base of a dining table? The sides of a bench? Sometimes, he still liked to think of himself as an engineer, but in truth he was a former math whiz who once taught high school math and chemistry while he saved for university, and who now worked as a carpenter and knick-knack maker who turned other people’s garbage into something of value.

He took the table apart, sawing and breaking the weakened wood, dousing it in gasoline, which he hoped would kill any remaining termites or at least stun them until morning when he could burn the piles of wood. He sanded the rust and paint from the scrolled metal, ran his fingers over the smooth surface he had revealed, then wiped it clean and painted it anew, brushing with quick strokes though he knew it was work best done in daylight when he could see the crevices he had missed, the bubbles of paint he failed to smooth completely. But he worked steadily through the night, moving his hands like a robot calibrated only

to move a brush back and forth.

That night, while he worked with the scent of sawdust and paint tickling his nose, he also broke down and rebuilt himself. He took the man Pauline had seemingly discarded, stripped bare his soul, tore apart every bit of his life, the one fact he couldn’t dispute—he hadn’t discouraged the girl from coming to his workshop—and began rebuilding a man who would indeed be valued. A man who had control over his own life.

While the paint dried, he sketched out the top of the table, trying to decide on a round or square top or a plank of wood that retained the uneven circumference of the tree trunk with its natural grooves and pockets intact. In the end, he chose the circular top with its natural characteristics erased.

By morning, when slashes of sunlight began appearing, when the dew drops still hung on the leaves, when Pauline emerged from the house and looked around the verandah and down the hill for a glimpse of him, he had a plan to save his soul and his family, to remake himself as a carpenter planes and sands and remakes wood, a plan that even the devil couldn’t mock.

He would become a priest, remake souls instead of other people’s discarded things, make up for his one great sin with a life of pious devotion. And make up for the one life he had irreparably wrecked—Plum’s.

He lay down on the sawdust, his nose against the scent he liked, and slept. By the time he woke, the sun was way overhead, the house above the workshop quiet. He brushed the sawdust from his body, cleaned up, bathed away the scent of sawdust and paint, and left for the Baptist Church in Mt. Carey. He took the narrow, rutted, and marl-filled road that emptied out onto the main road and continued along until he reached the slight hill upon which the Baptist Church stood. He waited for the pastor to come, his surety and confidence in his decision to swap his current life for the priesthood building as he waited in the shadow of a palm tree on the rocks that overlooked the stony graveyard. Somewhere below the church lay the bones of one or another of his relatives he hadn’t known and whose offspring he wouldn’t ever know. He wasn’t concerned with progeny, though. Instead, he was concerned with something else he had come to understand: what it meant to have agency, to have the capacity to exert power and control over his life. Despite the scandal threatening to disrupt his life, he felt he had agency, the power to choose another way of living. If he couldn’t teach or be an engineer or make do with the life he had built in Anchovy, he would become a priest. Engineering and the priesthood were one and the same, he thought; engineers built foundations for buildings, and priests, likewise, helped congregants build foundations in Christ.

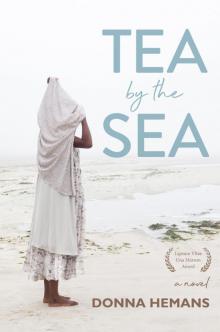

Tea by the Sea

Tea by the Sea