- Home

- Donna Hemans

Tea by the Sea Page 6

Tea by the Sea Read online

Page 6

Two weeks passed without Lenworth seeing Pauline, without their impromptu meetings at the bus stop. As quickly as the courtship began, he gave up the dream.

“Tell me again about my mother.” Opal was looking up at Lenworth, her face like a flower opening.

“What you want to know?”

“Where is her birdcage?”

“I don’t have that anymore.”

“Was she little like a parrot, or big like an ostrich?”

“Like an ostrich.”

“Ostriches can’t fly,” Opal said it so matter-of-factly, Lenworth thought she was testing the veracity of his story.

But she was much too young to connect the fantastical elements of his story about a bird woman with the reality of flightless birds.

“Where you learn ’bout ostriches?”

“Mrs. Wilson has a big book with lots of birds it. She said ostriches are too big to fly.”

“What else you learned at school today?”

“Nothing.”

Lenworth turned back to the pan of white shirts he had left in the sun to bleach the stains. Soap suds spread on his arms like a sprinkling of powder.

“If my mother was big like an ostrich, how did she fly away?”

Rather than answer, Lenworth took the clothes outside. “Go get a book and come and read it to me,” he said, as he was walking out. But inside his heart beat furiously. Sooner or later, he thought Opal would catch him in a lie and figure out for herself how unrealistic his story was.

A month passed before he saw Pauline again, not at the bus stop this time, but at Montego Bay High on the verandah outside the principal’s office.

He had been summoned, as he often was, to fix a broken chair or table, and he walked up to the administrative building with a tool bag. He whistled as he walked, forgetting for a minute that his voice carried, and the students, easily distracted, would look through the windows at him. Pauline stood on the verandah, breaking into a smile as he walked toward her.

“What you doing here?”

“Come to look for you.”

“You disappeared on me.”

“Just didn’t come out this way for a while. And since I never had any way to find you, I come up here to look for you.”

“Glad to see you.”

“Sometimes you have to take a chance,” Pauline said.

Lenworth knew without asking that she meant taking a chance with him.

“All right,” he said, and with that word it was settled.

Three days later, under a cloud-filled sky, Lenworth and Opal went by bus to Black River. Opal sat on Lenworth’s lap, her face to the window, her eyes glued to the shifting shades of green in the hillsides and the valleys, and her finger pointing out women walking to or from a market or farm with a full basket balanced perfectly on their heads. A cotta, a circular pad of banana leaves, the only thing between the baskets and their heads. She pointed to a donkey pulling a cart, a rarity in those days even for Lenworth. Through town after town, there was something else that held her gaze.

How little he had exposed her, Lenworth thought, and he realized that most of what Opal had learned outside of school had come from Sister Ivy.

“We soon reach?” Opal looked up at him, her eyes so brown, so like her mother’s that he looked away immediately.

“Soon.”

Pauline was there in front of the bakery as she had said. She led them to a taxi, which took them away from the sea and the river, up a road filled with potholes to a small community clinging to life. Chickens roamed the yard, pecking at the dirt, and from further away he heard the distinct squeals of a pig.

“Everybody waiting,” Pauline said.

Indeed, her parents were on the verandah, her mother standing with her back bent slightly as she leaned forward to hold up a tottering child. And her father, in an undershirt and stained pants, looked up at Lenworth with a probing gaze. Only then did he think he should have brought something, whether a bunch of bananas or plantains, or pears or breadfruits or a set of bowls he had made. Almost immediately he dismissed the thought, for he didn’t want her family to think he was buying their approval.

“Good afternoon, sir.” Lenworth held out his hand, pulled Opal forward. But she wouldn’t budge, simply stood behind him and peeped around his legs at the three strangers and baby.

One by one Pauline’s sisters came, and they too looked at him as if he were an unusual specimen or such a rarity for a sister to take a man home to meet the family.

“So, the little girl, what happen to her mother?” Pauline’s mother stopped cooing at the child long enough to ask about Plum.

“Died in childbirth,” he mouthed, and nodded thanks for the belated condolences. He had also come to expect the look of pity directed at Opal.

“Anchovy, eh? Long time I don’t go that way.” Pauline’s father spoke. “Used to go that way all the time. You know a fellow name Thomas White?”

“No.”

“He used to own an auto parts shop.”

“No. Can’t say I know him.” Lenworth’s heart quickened. He expected more questions like this, more indirect probing of his life and story. It wouldn’t take much, he knew, for his story to fall apart.

“He probably gone long time now.”

“Anchovy where your people from?”

How skillfully he got around the details. “Had a granduncle named Orville Ramsey, who had property out there from the '30s or early '40s. His house I living in now. Old house with problems, but when you starting out . . .”

On he went, sifting the truth, establishing himself as motherless and without siblings, a hard-working carpenter and general handyman. “Next time, I’ll bring you one of the bowls I make. Coconut shell,” he said. “So pretty when you polish it.”

But that would be Lenworth’s only trip to Black River. He left with Pauline, who packed her life into two bags and glided away from her parent’s house and her plump and satisfied sisters.

Pauline was nothing like Plum, an inadequate replacement really. Lenworth realized early on that the woman he had married was a version of his sister and mother. She had no independent goals; her identity now was simply wife. She had waited her whole life for this, not him necessarily, but a man to give her the role she thought she was groomed to play. At that moment, Lenworth was content to let her play that role, if only to give Opal the mother he thought she deserved, and hold at bay Opal’s questions about the bird woman who disappeared.

And even Opal seemed instinctively to know Pauline’s inadequacies. She would not smile at Pauline. Instead, like she did as a baby, she looked at the spaces around Pauline as if she still expected to see someone else there—a bird woman with wings, perhaps.

3

Plum lived her life in limbo, like a planet in orbit outside its solar system, waiting light years to fall back into its rightful place. Living and not living, waiting to be summoned back to Jamaica, dropping everything and going when called, coming back to Brooklyn empty-handed one, two, three times. Each time, she picked up little shards of Lenworth’s life, some pieces too small to matter, some large and useful, leaving her breathless.

On her third trip, one she took on her own without the summons of the private investigator, she stayed for four days in a cottage in Reading, a small town on the outskirts of Montego Bay and just off the main road to Negril. Three of the four days, she drove to towns along the coast—Falmouth, Ocho Rios, Port Maria—and into the hills, up to Brown’s Town where she and Lenworth had briefly lived, and on to Lluidas Vale and Linstead.

Eight years later, Mrs. Murray’s yard was much the same, like a garden painted by an artist, the blooms exaggeratedly bright. The flame of the forest trees that dwarfed the house were in full bloom. Where Mrs. Murray had had a hedge of roses, she now had ixora boasting small bunches of red and peach flowers. Spread around the yard were flowering bougainvillea and hibiscus, with red and pink and yellow blooms, and on the verandah were anthuriums, six of them, ea

ch with a rare purple flower.

“Look at you.” Mrs. Murray held Plum at arms’ length, then pulled her closer in a crushing embrace. “I so glad to see you.”

“Glad to see you too.”

“You hear anything?”

“Nothing yet.”

“Don’t give up hope, me chile. As they say, every dog have him day and every puss him four o’clock. His time soon come.”

Plum held out a small package. “A thank you. It’s not much, but it reminded me of you.”

“Thanks, me dear. I just glad to see that you didn’t just wither up and do nothing. That alone is a gift.”

Like a child, Mrs. Murray shook the box, undid the tiny bow. Inside, on a bed of crinkled tissue, was a corrugated copper cuff bracelet. “Oh. You know me too well.”

“Glad you like it.”

“Come inside. No use standing out here in the heat. I want to hear everything. Medical technologist, right? Sound so important.”

Immediately inside the doorway was a large painting of a woman sitting on a low wall with her head hanging low. Near the woman were two large monkey jars, a heavy wooden front door painted a shade of jade just like the one to the cottage where Plum had lived. The woman in the painting had no face, but the slump of her body told of despair. Plum stepped closer, tracing her fingers on the curve of the woman’s back. “That’s me, isn’t it?”

“Yes. I painted it the day after you left.”

“No face?”

“Sometimes the body says it all. And it’s the emotion I wanted to convey.”

“I see.”

“I painted one him, but it was the devil with two horns. Stereotypical.”

Plum laughed. “That he wouldn’t be able to tolerate.”

“Hope you don’t mind the painting. Everything in my life inspires me, the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

“Not at all. I like it. Puts my life in perspective, you know.”

“Good. Well, you know I like my tea. So let me make some and then we can chat. Mint or black tea?”

“Mint.”

They passed the afternoon like old friends, Plum reminding herself time after time how far she had come since Mrs. Murray returned her to her suspended Brooklyn life. Plum kept coming back to one thing: though she had indeed gone on and lived her life, a part of her life was still suspended, temporarily prevented from moving forward.

Except for the fact that Falmouth and Port Maria had well-known high schools where Lenworth could have sought work and the towns were close enough to Brown’s Town, Plum had no specific reason to think that he would have gone to either place. Nonetheless, Plum, in a sundress and ballet flats, walked along narrow sidewalks and shop piazzas with worn and shiny concrete steps, looking through supermarkets and shops, the outdoor markets with their pickedover discount goods, searching among the myriad faces with varying shades of brown skin for a man with eyebrows so thick they came close to meeting in the center of his face, and a goatee. She pictured him with a shaved head or hair cut low to minimize the balding dome.

Each supermarket was mostly the same—poorly-lit with shelves of Milo and Ovaltine and sweet spiced buns; flour, sugar, and cornmeal in clear plastic bags; soup mixes and sugared drink mixes; boxes of sweet potato and plantain (both ripe and green), the smell of thyme so strong she thought someone must have accidentally crushed a bunch under foot.

He always liked a bargain, loved the business of haggling down a price, loved to haggle just for the sake of it. But not Plum; she wanted a price, a fair one, and saw no reason she, or any customer for that matter, should expect to negotiate just for the sake of it. So she went to the outdoor markets where haggling was common and searched the faces of the shoppers, hopeful for a glimpse of him. It was a desperate act, really, and she knew the futility of such a search. But she felt compelled to do something, to look at random faces in random towns, hopeful for something that would end her years-long search.

And at the end of each evening, before beginning the long drive back along the coast to the cottage outside Montego Bay, she sat in the car with eyes closed concentrating on breathing deeply, counting each inhalation and exhalation as if breathing were a lesson one needed to be taught. One, two. One, two. She learned this in high school, how to hold back grief, how to not let disappointment overwhelm, but promptly forgot that lesson immediately after Lenworth disappeared. Immediately after Lenworth left, and even now, she let the grief rip her apart, let the tears and the screams come rather than bottling them inside. But now she breathed and trapped her grief, one, two. One, two. One, two.

Composed at last, eyes and cheeks dry. She looked in the rearview mirror and smiled, a slight reminder that everything would be all right. Then Plum was on her way back on the winding hillside roads—looking from the hilltop for the azure waters and white sands emerging as if they’d been hidden behind a curtain—cruising along coastal roads that bifurcated swamps, with the air conditioner off and the breeze whipping around the car; flying past the road to her aunt’s house in Lakeside Park, thinking that she should stop and visit, thinking too of her aunt’s direct and indirect reminders of Plum’s youthful missteps, but continuing past the road to the anonymity of the cottage in Reading.

Driving around like that reminded Plum of day trips she took with Alan in his parents’ car to towns outside of Brooklyn—along the coast of Long Island, the New Jersey shoreline, upstate New York, and south to Delaware and Baltimore and Maryland’s eastern shore. Alan wanted to see how others lived outside the confines of a concrete city, and Plum went along, partly to escape her parents. Plum and her parents lived two separate lives. Fully an adult, she lived in their house as if she was still waiting to belong to them again, waiting for them to welcome her fully back in their lives. They had. But Plum, still feeling like the girl abandoned on the island, still feeling like the girl abandoned in the hospital, kept her life distinctly separate from theirs.

Whenever Alan presented an escape, Plum accepted, knowing all the time that his motivations differed from hers. Alan was persistent, but not pushy. He never called them dates, just drives. They would sit in the bridge walkway that connected two buildings on campus, with a map between them, and pick a town within a fourhour drive. Plum packed sandwiches and drinks, and they’d leave early on a Saturday morning, just when the city was beginning to wake. Between them, they had just enough money for gas and tolls, nothing for emergencies, nothing for extra activities.

They talked about everything and nothing, Plum more careful than carefree in what she revealed about herself, cryptic even.

Once, Alan asked, “Why do you hate men?”

“Why do you think I hate men?”

“Well, maybe not men. Why do you hate me?”

“I don’t hate you. I wouldn’t be here with you in a town where I don’t know anybody if I hated you.” She paused. “Only one person I can say with absolute certainty that I hate.”

“Why? What did he do to you?”

“You assume it’s a man.”

Alan laughed. “Yes, I know it’s a man. What did he do?”

“Too long a story to tell.”

“Two more hours before we reach. You have plenty time.”

Plum turned to the window, her gaze on the vehicles whizzing past in the opposite direction, working through how to tell Alan about Lenworth and her lost child. But she didn’t know where to begin, how to say without crying exactly what the mystery man had done and why, what specifically she was carrying with her and would carry with her forever. It’s simple, she wanted to say. He took my daughter. But there was nothing simple about it, not the actual taking of the child, not the way he left her, not the heartache, the fruitless searches. She wiped away a tear and turned her head back to the passenger window.

“You don’t have to talk about it if you don’t want to.”

She didn’t. The moment lengthened, the silence becoming increasingly uncomfortable.

“You’ll tell me one day for sure.”<

br />

“How you so sure ’bout that?”

“Because one day, you’re going to marry me. And when I’m your husband, you will tell me everything.”

“You so sure of yourself.”

“At least I made you smile.”

Plum did indeed smile, but even then she knew that underlying Alan’s lighthearted shift of the conversation were his deep feelings for her.

On another of those day trips, three years after they’d first met in a biology class, Alan had asked, “Why don’t you just marry me?”

They were on Chincoteague Island, along the Virginia shoreline watching for the famous wild ponies. Plum didn’t care for the ponies, the swarms of wild birds, or the flat, brackish land. When she thought of an island, she pictured palm and coconut trees, a yard with an almond tree, white sand beaches, cliffs rising up from the ocean, a blue rather than black sea spread out before her.

Plum waited a moment, reached for Alan’s hand. “Ask me again in a year,” she simply said, prolonging the cat and mouse game, dangling herself but not committing to anything at all.

Plum’s reason was simple: She wasn’t ready to open herself up to the possibility of another heartbreak. She had rightly concluded from Alan’s persistence that he would wait. He did indeed ask a year later after they had graduated, and another year later, and each time Plum moved the goalposts another year out. “Give me another year. I want to know for sure because there is no leaving after.” That Plum was certain about, she didn’t want to be left again. And there was no room in her heart or her soul just yet to love another the way she had loved Lenworth.

Plum spent her last day in the cottage at Reading—a lazy Sunday—on the beach sifting through the sand for intact shells she planned to stack in bottles with sand. That evening, her hair damp and skin tingling from overexposure to the sun, Plum sat on the verandah with a small transistor radio by her side. A man’s deep baritone came across. She preferred music to the talk shows, a preference honed during her teen years in Jamaica. In a sense, it was defiance. Plum hated what her aunt liked, and her aunt liked to listen to the numerous calls and complaints—whether about potholes, a fire station without a fire truck, firefighters who couldn’t or wouldn’t come to a burning house because they lacked water, the day’s political scandal. The complaints all sounded the same. Years later, Plum knew she would come to the same conclusion she had as a teen: no matter the political party in power, the government had failed its people.

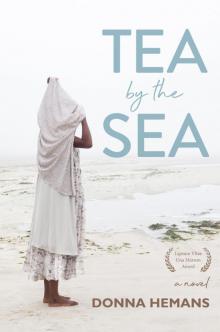

Tea by the Sea

Tea by the Sea